October: Fun, Sharp-eyed Feminism + Award-winning Kid Lit

Nawara Negm is the daughter of Egyptian literary royalty (Safynaz Kazem + Ahmed Fouad Negm) and her debut novel is so much better than you could've expected.

Apologies for being late this month. Among other things, we are hard at work on translations of the 15 short stories that were finalists for our 2024 Arabic Flash Fiction prize. More about those exciting writers (with excerpts, interviews, & more) in next month’s email.

📚Featured Fiction: Nawara Negm’s You Have Been Blocked

Nawara Negm is the daughter of two of Egypt’s most towering literary and critical figures.

So first, her famous mother:

Nawara’s mother is the great Safynaz Kazem, and if you’re interested in translating a classic, you should check out her Romantikiyaat; we ran an excerpt of it in the Winter/Spring 2020 issue of ArabLit Quarterly, and it’s a recommended read from no less than the great Iman Mersal. You can read an excerpt on our website. From that excerpt, tr. Hadil Ghoneim:

New York, August 17th 1965

My birthday. Alone in the room…preparing myself for a feast of daydreams… The others don’t understand, the others being my serial roommates, “Let’s do something.” Why do they insist on tying their boats to mine? I’ve always meant to keep my boat free, to follow only what occurs to it without the burden of explaining and answering questions and racing and group outings. The truth is I have nothing to explain, and my answers never convinced anyone in the past. I had to lie to make my answers sound more reasonable. I didn’t have the money for the race. I am arrogant because I like to be virtuous. Sorry.

Hadil also writes about Safynaz’s life in the excellent “Fallible Men vs. Safynaz Kazem.”

And second, her famous father:

Ahmed Fouad Negm (1929–2013), popularly known as Al Fagoumy, was one of Egypt’s most popular poets. The first poet to write in colloquial Egyptian, he was known for his satiric verses mocking rulers and others in power. In the 1960s he collaborated with Sheikh Imam Eissa, a composer and oud player, who set Negm’s verses to music, such that they became popular worldwide. (A biopic was released in 2011, although not not much acclaim.)

You can read his “Important Announcement,” translated by Elliott Colla.

And now, Nawara Negm:

Nawara Negm is an Egyptian journalist, writer, and one-time blogger based in Cairo, Egypt. She works as a translator and news editor but grew popular through her blog, “Popular Front of Sarcasm.” She has previously published several books: a collection of her essays; an anthology of work by women authors, I Am Female; and a 2023 memoir about her relationship with her father, And You're The Reason, Dad. However, You Have Been Blocked is her first (fiercely funny and fiercely feminist) novel.

Here, from the excerpt beautifully translated by James Scanlan:

She looks in the rear-view mirror and sees a line of cars honking in outrage. Sahar nods at the man, and his bearing shifts so that he erupts like a drill sergeant with commands of “To me!” and “To you!”

Sahar collects her things in a hurry—phone, earphones, cigarettes—and puts them in her oversized handbag. She exits the car with the aim of asserting some distance between herself and That Spit.

“You will leave the key fob,” he says, as if reading from a transcript. Further spools of spittle fly with the “f” of “fob”. Sahar leaps back, and the man attempts a reassuring smile, which sets forth a band of broken black teeth: the orbiters of a single silver incisor. He introduces himself as “Hassan, the doorman for that building over there.”

Sahar removes the fob from a chain strung with so many keys to so many forgotten doors. She hands it to Hassan, and his rough fingers chafe against hers as she does so. He asks how long she’ll be away. She tells him she’s going to the Internet Complaints office, and he responds with invocations of “La hawla wala quwwata illa billah” and “Hasbi Allah wa na’m al-wakeel,” cursing the sort of godless bastard who could harm a poor, defenseless woman.

She ignores this and asks which way to walk. He raises an arm to the end of the street, and an aroma of chickens blows from within.

Sahar walks quickly in the direction Hassan pointed out; she’s already late for Mamdouh, her lawyer.

The eyes of a boy no older than twelve communicate the rise and fall of her breasts. She pulls up her shirt and strides on, head to the ground, oblivious.

Calls of “You beauty!” pursue her, regardless.

She crosses the road through a line of stationary cars by traffic lights. Mamdouh is waiting for her, smartly dressed in a full suit. They shake hands and Sahar apologizes for being late, smiling, irritable. The smell of lavender hits her. Mamdouh’s shaving cream, presumably. He uses the same one as her ex-husband Ashraf. She feels nauseous again and—this time—doesn’t retch.

Mamdouh gestures for her to go ahead. Sahar hesitates at first but goes ahead anyway, then falls into step behind him when he starts walking. Better that way—for protection. She won’t have to keep pulling up her shirt. The plan crumbles under the probing gaze of the man by the automatic doors. She pulls up her shirt. Mamdouh walks on imperatively, and Sahar follows, eyes down.

“YES?” the man announces.

“Internet Complaints,” Mamdouh says.

The man points to the only conceivable way they could possibly proceed. Sahar catches up with Mamdouh to ask why the man by the door had said “YES?” like that. But she knows the answer already: it’s not easy earning a living as a doorman to an automatic door. One must create side quests for one’s own amusement, such as giving directions to people who don’t solicit them.

The pair climb a set of steps to reach the building’s entrance. To the left of the door, a young man is sitting behind a desk. As they walk toward the lift, he calls after them, “YES?”

“Internet Complaints,” Mamdouh says.

“Floor eight,” the young man says.

“Thank you, sir.”

Read the whole excerpt at ArabLit. Rights are with Dar El Shorouk; you can be put in touch with the translator (and thence the publisher) by contacting us at info@arablit.org.

📚The Etisalat Award for Arabic Children’s Literature

Also this month, the Etisalat Award for Arabic Children’s Literature, one of the biggest prizes for literature for young readers, announced their shortlists in five categories: early readers, picture books, poetry, young adult literature, and chapter books. The list features several returnees — Egyptian illustrator Sohaila Khaled and Palestinian illustrator Baraa Alawoor, among others — as well as publishers, authors, and illustrators new to the prize.

Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp has put together some highlights over at ArabKidLitNow!

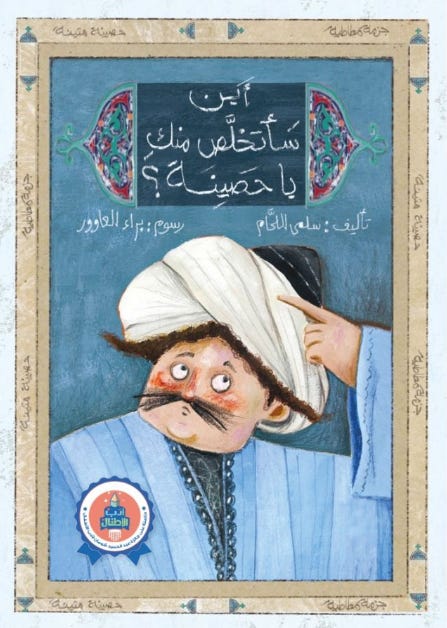

Some we’re particularly looking forward to seeing are the middle-grade novel ابنة غواص اللؤلؤ وعقد البَعو (A Pearl Diver’s Daughter and the Cowrie Necklace) by Maitha Abdulwahab al-Khayat; the middle-grade novel لغز اللافندر (The Mystery of the Lavender) by Abir Adel Ahmed, illustrated by Sama Shabout; and the chapter book أين سأتخلص منك يا حصينة؟ (Oh, Where Am I Going to Dump You, Hasinah?) by Salma al-Lahham, illustrated by multi-award-winning Gazan artist Baraa al-Awoor.

Reach out to us for samples and more.

💰Grants, subsidies, & support

Don’t miss LEILA’s list of grants, subsidies, and support on their website.

The Sheikh Zayed Book Award offers a significant subsidy for shortlisted titles in the children’s and literature categories. They should be announcing their 2024 longlists soon.

If you know of grants or subsidies targeting Arabic literature, please let us know at info@arablit.org.